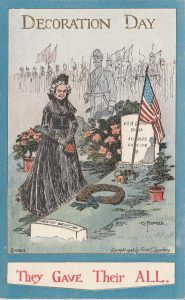

It was 1866 and the United States was recovering from the long and bloody Civil War between the North and the South. Surviving soldiers came home, some with missing limbs, and all with stories to tell. Henry Welles, a drugstore owner in Waterloo, New York, heard the stories and had an idea. He suggested that all the shops in town close for one day to honor the soldiers who were killed in the Civil War and were buried in the Waterloo cemetery. On the morning of May 5, the townspeople placed flowers, wreaths and crosses on the graves of the Northern soldiers in the cemetery. At about the same time, Retired Major General Jonathan A. Logan planned another ceremony, this time for the soldiers who survived the war. He led the veterans through town to the cemetery to decorate their comrades’ graves with flags. It was not a happy celebration, but a memorial. The townspeople called it Decoration Day.

In Retired Major General Logan’s proclamation of Memorial Day, he declared: “The 30th of May, 1868, is designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers, or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country and during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village and hamlet churchyard in the land. In this observance no form of ceremony is prescribed, but posts and comrades will in their own way arrange such fitting services and testimonials of respect as circumstances may permit.” The date of Decoration Day, as he called it, was chosen because it wasn’t the anniversary of any particular battle.

In Retired Major General Logan’s proclamation of Memorial Day, he declared: “The 30th of May, 1868, is designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers, or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country and during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village and hamlet churchyard in the land. In this observance no form of ceremony is prescribed, but posts and comrades will in their own way arrange such fitting services and testimonials of respect as circumstances may permit.” The date of Decoration Day, as he called it, was chosen because it wasn’t the anniversary of any particular battle.

This is written to commemorate the lives of Tiverton men and women who served in the Civil War (or the Rebellion, as it was also termed), highlighting Julia Chace Osborn Burdick, Isaac H. B. Cook, Corporal Franklin S. Gray, Horatio Nelson Humphrey, Philip Mosher, Green Tripp, and Webster Wordell.

Julia Chace Osborn was born in Tiverton on April 11, 1828 to Thomas and Ann Durfee Osborn. She married Rev. David M. Burdick and had two children: Carrie L. Burdick and David J. Burdick (who married a Babbitt).

Julia Chace Osborn was born in Tiverton on April 11, 1828 to Thomas and Ann Durfee Osborn. She married Rev. David M. Burdick and had two children: Carrie L. Burdick and David J. Burdick (who married a Babbitt).

At the start of the Civil War, there were no organizations of trained nurses in the United States. During the Crimean War of 1854, England’s Florence Nightingale laid the foundation for trained nursing care to support not only the physicians and surgeons, but to help with the sanitary, social, and psychological needs of servicemen. Her work cleared the path for middle and upper class women to seek a nursing career as an acceptable lifestyle. Women played a significant role in the Civil War. They served in a variety of capacities, as trained professional nurses giving direct medical care, as hospital administrators, or as attendants offering comfort. Although the exact number is not known, between 5,000 and 10,000 women offered their services. Among these were renowned Dorothea Dix, Clara Barton, Louisa May Alcott, and Mary Ann Ball (a.k.a. Mother Bickerdyke).

Unfortunately, we could not find the war records of Julia, so we are not sure where she was stationed during the Civil War as a nurse, only that she served as one from the statement on her headstone: “Army nurse in the Rebellion.”

Julia died on November 8, 1899 from a chronic obstruction and is interred in the Osborn family burial ground, Historical Cemetery #43.

Isaac Hodges Bennett Cook enlisted in Company A Rhode Island Volunteers 4th Infantry Regiment on August 16, 1862 as a Private. This regiment was in the battles of South Mountain in Maryland, Fredericksburg, and Antietam, as noted on the marker there: On the morning of the 17th, Harland’s Brigade moved from its position southeast of Burnside Bridge. The 11th Connecticut, deployed as skirmishers, preceded Crook’s Brigade in its assault on the bridge and was repulsed with great loss. During the forenoon the remaining Regiments of the Brigade moved down the left bank of the Antietam, crossed at Snavely’s Ford and, moving up the right bank of the stream, formed line on the left of the Division, Ewing’s Ohio Brigade in support. At about 3 P.M., the Brigade advanced in the direction of Sharpsburg. The 8th Connecticut passed to the west of this point and the 16th Connecticut and 4th Rhode Island were in the 40 acre cornfield east, when they were attacked in flank by the right of A.P. Hill’s Division and compelled to retire to the cover of the high ground near the bridge.

Isaac Hodges Bennett Cook enlisted in Company A Rhode Island Volunteers 4th Infantry Regiment on August 16, 1862 as a Private. This regiment was in the battles of South Mountain in Maryland, Fredericksburg, and Antietam, as noted on the marker there: On the morning of the 17th, Harland’s Brigade moved from its position southeast of Burnside Bridge. The 11th Connecticut, deployed as skirmishers, preceded Crook’s Brigade in its assault on the bridge and was repulsed with great loss. During the forenoon the remaining Regiments of the Brigade moved down the left bank of the Antietam, crossed at Snavely’s Ford and, moving up the right bank of the stream, formed line on the left of the Division, Ewing’s Ohio Brigade in support. At about 3 P.M., the Brigade advanced in the direction of Sharpsburg. The 8th Connecticut passed to the west of this point and the 16th Connecticut and 4th Rhode Island were in the 40 acre cornfield east, when they were attacked in flank by the right of A.P. Hill’s Division and compelled to retire to the cover of the high ground near the bridge.

Cook was transferred to a new regiment, Company G 7th Rhode Island Volunteers, on October 21, 1864. This Company saw several skirmishes, including the battle of Fort Stedman, the Appomattox Campaign, and the pursuit of Lee to Farmville. He mustered out June 9, 1865 with the rest of his regiment.

Isaac was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts on July 6, 1844. He married Sarah Petty, and after she died, married Cornelia Jane Bliss (who was widow of a Paquin and a Reed).

He is described in early records as being a tailor, and in later records, as a fisherman. He died in Tiverton on April 12, 1905 and is buried in the David Rounds plot, Historical Cemetery #16.

Franklin Seabury Gray, son of John Gray & Susan Seabury, was born on November 29, 1844 and died at Cold Harbor, VA on June 3, 1864. He was a sailmaker by trade.

Franklin Seabury Gray, son of John Gray & Susan Seabury, was born on November 29, 1844 and died at Cold Harbor, VA on June 3, 1864. He was a sailmaker by trade.

Gray enlisted in Company E, Massachusetts 58th Infantry Regiment on March 1, 1864 at age 19. He was promoted to full corporal. It is assumed from his tombstone (Congregational Church Cemetery, Historical Cemetery #11) and war record showing he “mustered out” on June 3, 1864, that he perished in the Battle of Cold Harbor.

Continuing his relentless drive toward the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, General Ulysses S. Grant ordered a frontal infantry assault on General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate troops, who were now entrenched at Cold Harbor, some 10 miles northeast of Richmond. Minor skirmishes followed by delays began on May 31st, but the main attack occurred on June 3rd, when Grant launched a frontal assault on Confederate defenses. He believed that Lee’s men were overextended, but Lee had taken advantage of a delay in Grant’s assault to bring in reinforcements and improve his fortifications. The result of his preparations was carnage; the advancing Union troops were soon felled, with those making it through the first line of defenses soon being slaughtered at the second. More than 7,000 Union troops were killed or injured in one hour before Grant halted the attack. Grant’s comment on the battle: “I regret this assault more than any one I have ever ordered.”

The result was Lee’s last major victory of the war and a bloodbath for the Union army. This battle was a disastrous defeat for the Union Army that caused some 18,000 casualties.

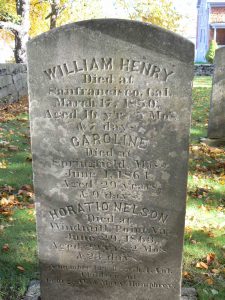

Horatio Nelson Humphrey was born on November 6, 1841 to George Washington and Mary Durfee Humphrey. Among his eight siblings, Peleg, George, and William were predominant in the Town of Tiverton.

Horatio Nelson Humphrey was born on November 6, 1841 to George Washington and Mary Durfee Humphrey. Among his eight siblings, Peleg, George, and William were predominant in the Town of Tiverton.

Horatio enlisted as a Private on October 5, 1862 in Company K of the 12th RI Infantry Regiment. Less than a year later, he died in the hospital at Windmill Point, Virginia on January 29, 1863, and is buried in the family plot on Nanaquaket, Historical Cemetery #2. This date implies he may have been fatally wounded in the Battle of Fredericksburg. The 12th Regiment was under fire for the first time at Fredericksburg.

Burnside assumed command of the Army of the Potomac in November of 1862 after McClellan failed to pursue Lee into Virginia. Burnside planned to move against the Confederate capital of Richmond. This called for a rapid march by the Federals from their positions in northern Virginia to Fredericksburg on the Rappahannock River. He planned to cross the river at that point and then continue south. However, due to poor execution of orders, a pontoon bridge was not in place for several days. The delay allowed Lee to move his troops into place along Marye’s Heights above Fredericksburg. The Confederates were secure in a sunken road protected by a stone wall, overlooking the open slopes.

Despite his field disadvantage, Burnside decided to attack anyway. On December 13, he hurled 14 attacks against the Confederate lines. Although the Union artillery was effective against the Rebels, the 600-yard field was a killing ground for the attacking Yankees. A bitterly cold night froze many of the Union dead and wounded. Burnside considered continuing the attack on December 14, but his subordinates urged him to stop. On December 15, a truce was called for the Union to collect their dead and wounded soldiers.

Union: 12,650 killed and wounded; Confederates: 4,200 killed.

Phillip Mosher was born in Warren in 1847 to Philip and Sophia Ann Lake Mosher. He enlisted as a Private in Company B, 4th Massachusetts Calvary Regiment in the Civil War.

Phillip Mosher was born in Warren in 1847 to Philip and Sophia Ann Lake Mosher. He enlisted as a Private in Company B, 4th Massachusetts Calvary Regiment in the Civil War.

The Second Battalion (Companies A, B, C, and D) sailed from Boston for Hilton Head, S.C. on the steamer Western Metropolis on March 20, 1864, arriving on April 1st. They conducted picket and outpost duty at Hilton Head until June. Two Companies moved to Jacksonville, Florida in early June, and participated in a skirmish at Front Creek on July 15, 1864, and another from Jacksonville upon Baldwin July 23-28. Other skirmishes occurred at South Fork, Black Creek on July 24th and at St. Mary’s Trestle two days later. They raided the Florida Railroad on August 15-19, and fought at Gainesville on August 17th.

Mosher was captured at Gainesville and was confined to the Andersonville, Georgia Prison where he died of starvation, according to his grave marker. This stone in Historical Cemetery #23 may be a memorial to his life.

From a personal recollection of Charles Smith of Company E, Massachusetts Cavalry, imprisoned there in March of 1864: 31,000 men in a pen, on the bare earth, exposed to the fierce rays of the southern sun, the drenching showers, the cold night dews, covered with vermin and sores….Neither shade nor shelter was afforded us, nor clothing issued…Some had been in prison many months, and were reduced by starvation and wasted by disease….Crowding and filth were nearly as fatal to the prisoners as starvation….Through the center…ran a filthy sluggish stream, four or five feet wide and six inches deep. This stream, which was the receptacle of the offal and filth of our camp, a Confederate camp, and the prison cook-house, was our water supply….The original inclosure[sic] contained…about 12 Acres; and this, when the number of prisoners was greatest (31,000) gave to each man about 17 square feet…The number of square feet required for an ordinary adult’s grave is about the same.

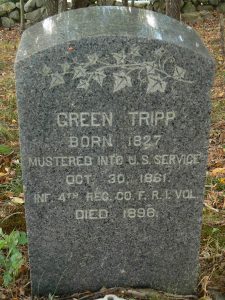

Green Tripp was born in Tiverton in 1827 to Rufus and Adeline Manchester Tripp. He enlisted as a Private on October 30, 1861 in the Infantry, RI 4th Regiment Company F in the Civil War.

Green Tripp was born in Tiverton in 1827 to Rufus and Adeline Manchester Tripp. He enlisted as a Private on October 30, 1861 in the Infantry, RI 4th Regiment Company F in the Civil War.

The 4th Company was attached to Howard’s Brigade, Sumner’s Division of the Army of the Potomac in November of 1861, and less than a month later was assigned to Parke’s 3rd Brigade in Burnside’s Expeditionary Corps. They moved to Annapolis the beginning of January and took part in the Battle of Roanoke Island on February 9, 1862. They advanced to New Berne and fought there on March 14th. They were then attached to the 1st Brigade, 3rd Division of North Carolina and began a siege on Fort Macon, capturing it on April 26th. The Company moved to Newport News, Virginia and was attached to the 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, 9th Army Corps of the Army of the Potomac. In August, they went to Fredericksburg, Brook’s Station, and Washington, D.C. September began the Maryland Campaign, beginning with the Battle of South Mountain on the 14th.

South Mountain divided Maryland from north to south, and this battle put Robert E. Lee’s Confederates against George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. Lee had just won the battle at Second Bull Run, and knew that McClellan was a slow and cautious commander. What he didn’t know was that McClellan had been provided with a copy of Lee’s orders and intentions. With this knowledge, he moved faster than Lee expected, and Lee barely had enough time to gather his forces along the banks of Antietam Creek.

The Battle of Antietam took place on September 16-17, and took a toll on the Union regiment: 21 enlisted were killed, 5 officers and 72 enlisted were wounded, and 2 men missing. Quoting from the War Department marker to Harland’s Brigade on the Antietam battlefield: On the morning of the 17th, Harland’s Brigade moved from its position southeast of Burnside Bridge. The 11th Connecticut, deployed as skirmishers, preceded Crook’s Brigade in its assault on the bridge and was repulsed with great loss. During the forenoon the remaining Regiments of the Brigade moved down the left bank of the Antietam, crossed at Snavely’s Ford and, moving up the right bank of the stream, formed line on the left of the Division, Ewing’s Ohio Brigade in support. At about 3 P.M., the Brigade advanced in the direction of Sharpsburg. The 8th Connecticut passed to the west of this point and the 16th Connecticut and 4th Rhode Island were in the 40 acre cornfield east, when they were attacked in flank by the right of A.P. Hill’s Division and compelled to retire to the cover of the high ground near the bridge.

Green Tripp was wounded in this battle on the 17th, was medically discharged on April 27, 1863, and returned home to Tiverton.

Webster Wordell was born on January 27, 1836 in Little Compton to Eli Wordell and Lydia Ruth Tripp. He had six brothers and one sister, Mary. He was working in Taunton as a carpenter when he enlisted on June 15, 1861 in Taunton, and was immediately ranked Corporal in Company F, Massachusetts 7th Infantry Regiment.

Webster Wordell was born on January 27, 1836 in Little Compton to Eli Wordell and Lydia Ruth Tripp. He had six brothers and one sister, Mary. He was working in Taunton as a carpenter when he enlisted on June 15, 1861 in Taunton, and was immediately ranked Corporal in Company F, Massachusetts 7th Infantry Regiment.

In July of 1861, the Regiment was ordered to Washington, D.C. as part of its defense units, so their ship left Boston on July 11th. In March 0f the next year, it was attached to the Army of the Potomac and marched to Virginia, where it took part in the battles at Yorktown in April, and Williamsburg in early May. Late May/early June saw the Regiment in the battle at Fair Oaks, Seven Pines, and later in June and July took part in several other skirmishes in the same area.

At the date recorded as his death on Wordell’s gravestone, the Regiment was on its way to Alexandria. Since the military records show he died on August 26, 1862 at G.H. Davids’ Island, New York, our supposition is that he got sick on the ship on his way south and they left him in the General Hospital at Fort Slocum which was on Davids’ Island, located in the western end of Long Island Sound in the city of New Rochelle. He died of diarrhea. We also don’t know if his body was shipped back to his family or not; this stone may be just a memorial to him by his family in the Stone Church plot, Historical Cemetery #8.

So when you come across a grave of one of our Civil War/Rebellion veterans, please take a moment and remember what they went through at that tumultuous period in our nation’s history. And then thank them for the freedom you have today living in the country they loved, united once more.